I been a long time leaving but I’m going to be a long time gone. Willie Nelson

Willie Nelson came to town with the Outlaw Music Festival. One might very well ask, why? At eighty-five years old, why doesn’t he put his feet up. Does he really have anything left to say?

Who knows? Why not ask, what is art? When does one know when one is an artist? More to the point, when does one know to quit? When you are young and smitten with the arts, it’s a question one ponders daily. One looks for confirmation, external or internal, to claim right to that title.

In time, one comes to know that there is no single answer. Some confuse profession and art and apply financial markers. People who sell their work for cash are artists- no matter how bad or patently commercial it might be.

In time, one comes to know that there is no single answer. Some confuse profession and art and apply financial markers. People who sell their work for cash are artists- no matter how bad or patently commercial it might be.

Other apply terms of frequency. Real writers write every day.

Others apply other more obtuse terms.

Some people, such as myself feel that such a term can only be answered by the seeker itself. If you are an artist, one day you’ll produce art and recognize same and you’ll know that you are an artist and you will continue to honor that badge and you will continue to do what is needed to produce art.

One day you will look at your art and say to yourself, “I am an artist.”

This is not the only criteria. Real art, myself and Mark Messerly, agree touches the heart and/or soul; real art creates an effect much like stepping on a third rail.

Mark’s a musician and writer. Among other thing he plays with the band Wussy. Mostly to me he’s a long time friend. I was writing about his band recently and sent him some questions.

In part, on another topic, he wrote that:

The greatest compliment we give to anyone [another artist] is to term them a lifer. Doesn’t fucking matter if you’re any good or draw flies, it matters that you’re going to be hauling gear into shithole clubs in an ice storm in February forever and that’s just how it is. You either love grinding out songs in unheated practice space or you don’t. Actually that is my favorite part of being in a band.

Taken to its extreme this can mean that real artists work till they die and few other things in life- beyond family, friends, other people’s art etc, matters.

Willie Nelson, like others of his generation ( such as Outlaw Fest co-founder Neil Young; and writer Anthony Bourdain) apparently agree with Messely’s defination and (have) made up their minds to die on the road. Dylan has obviously also make this choice.

This version of the festival was opened by the The Whiskey Daredevils at 4:00. They didn’t seem to care about their horrid time slot, they turned in an entertaining and professional set. They’re clearly pros if not lifers.

This version of the festival was opened by the The Whiskey Daredevils at 4:00. They didn’t seem to care about their horrid time slot, they turned in an entertaining and professional set. They’re clearly pros if not lifers.

The Devils were followed up by The Head and the Heart who shouldn’t have been on the bill. They dressed shockingly bad and played a set of banal indie rock.

The Old Crow Medicine show came out and played a fun, inspired and heartfelt set. The worst you could say about the Crow’s set is that if you’ve seen them once, you’ve seen this show. Which is fine, I could see their show once a year and be content. They’re a band clearly composed of lifers.

The Old Crow Medicine show came out and played a fun, inspired and heartfelt set. The worst you could say about the Crow’s set is that if you’ve seen them once, you’ve seen this show. Which is fine, I could see their show once a year and be content. They’re a band clearly composed of lifers.

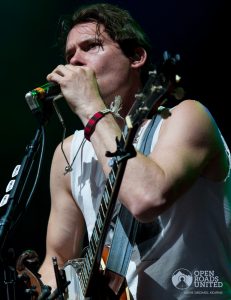

Sturgill Simpson came out and played a vicious hell bent for leather show. I last saw Simpson four years ago when he was the face of esoteric country; the new white hope of classic Nashville. Since then, he has apparently decided to spend a lot of time in the gym.

Simpson’s a much larger man now and has decided to forgo the strange in favor of shredding. A drummer and friend once said that there are two kinds of musicians: motherfuckers and Motherfuckers.

Sturgill, four years ago, was a damn fine musician. He’s now a Motherfucker fronting a group of bad-ass Motherfuckers. While Simpson shredded, stopping only long enough to sing a verse, his drummer played like a beast, his bass player sat deep in the pocket and his organ player did everything but set fire to his Hammond B-3.

It’s telling that just prior to the show, Simpson, via management, told the dozen professional photographers there to shoot his show they would have to photograph from the soundboard-located about 100 feet from the stage- rather than from the pit just before the stage. Lacking a long lens, I stashed my camera equipment and watched from the pavillion with friends. This was my good luck. Simpson clearly called this production audible because he didn’t want to risk an interruption or distraction, he clearly had something to say. Watching the set from start to finish made me very happy.

In short, his set was the best I’ve heard in a very long time. It was not what I expected, but I was glad to see it. I can’t wait to watch him grow as an artist.

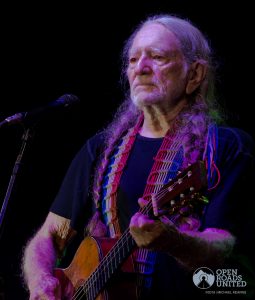

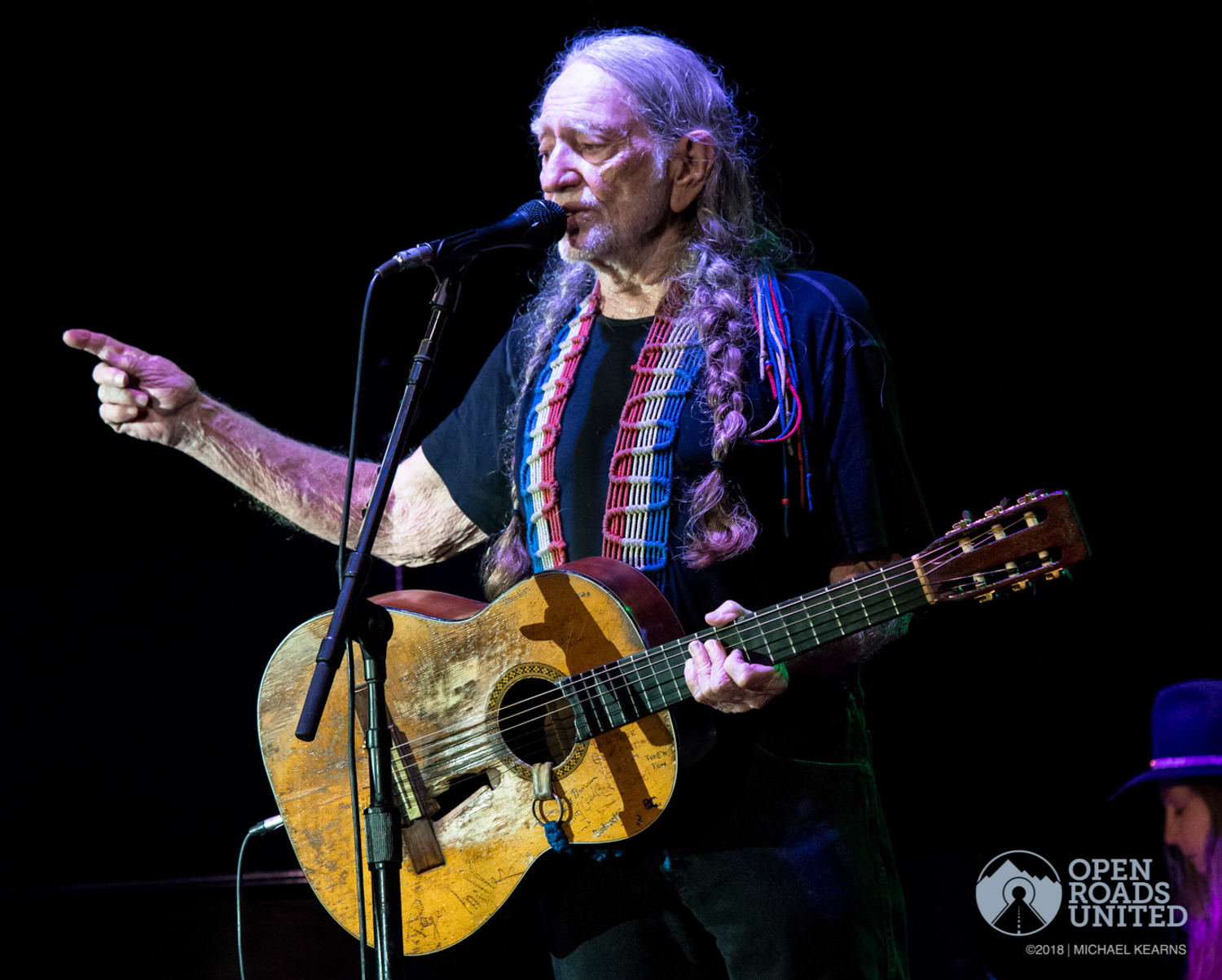

Onto Willie, who appeared from stage left, shrunken, emaciated and gray under his iconic white cowboy hat, standing behind Trigger. I’d last seen Nelsen, also four years prior, at the now defunct Buckle Up Festival in Cincinnati.

No one photographed Nelson this night, photos were forbidden, thank God. I don’t know if I would have had the heart.

Four years ago I was one of a handful of people backstage when he walked from his bus to the stage (I worked for the festival). I saw him clearly and photographed him that night. He was old then, but played well. His voice hung with the music, road the hills and valleys of the falling and rising notes, met the harmonies of his band.

This night his voice was flat and one song sounded much like the next, there were few discernible change in time, no rising and falling with the song’s tide. He was a very old and slow and broken tour bus fighting his way into the heavy winds of the plains. He looked much like Ralph Stanley on his final tour: small and well past pale, determined to die with his boots on.

Both sets were painful and courageous acts.

Mostly the Nelson and Stanley sets were lessons in what it means to dedicate one’s life to one’s art, lessons in what it means to be a lifer. To any artists in the audience it was likely a challenge that shook the foundations of one’s heart soul and commitment. I found it too painful to watch and left after a half dozen songs, my heart aching.

So be it. If Nelson has earned anything in this life, after 200 albums and sixty years on the road, it’s his right to call his own final shots. And if that’s too much for some of us, tough luck.

I do hope his final trail is a good one and I thank him for the songs and lessons taught this night. I hope some day to own half as much courage.